15 Jul 2025

Image: nuraann/ Adobe Stock

The assessment and treatment for brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome (BOAS) has progressed over the past 10 years.

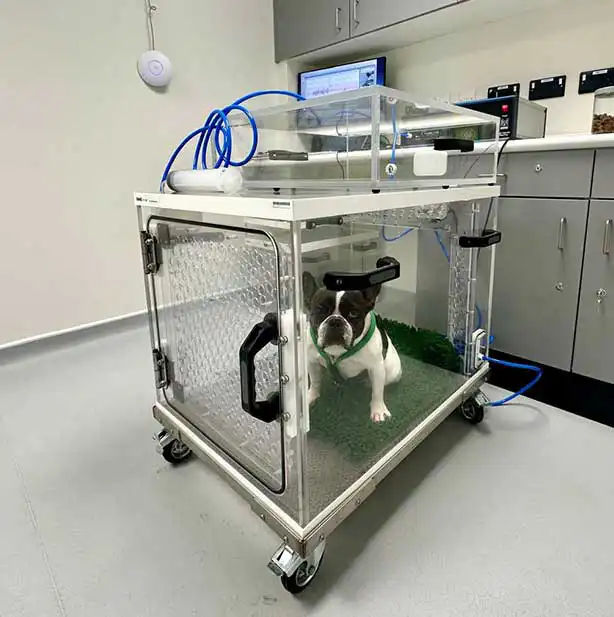

Now, instead of a straight palate trim and wedge nasoplasty for all brachycephalic dogs, we can tailor treatments to lesion sites and severity. At Granta Veterinary Specialists, we use the whole-body plethysmograph (Figure 1), which is non-invasive for BOAS assessments and, by looking at three different markers of respiratory obstruction, we can assess respiratory flow traces1.

This test has been further developed to give a BOAS index for the bulldog, French bulldog and pug a numerical score from 0% to 100% to describe how severely an individual dog is affected with BOAS, where 0% is non-affected and 100% is our most severely affected individuals.

The BOAS index is important, as we now have an objective measurement with which to evaluate risk factors for BOAS and the effectiveness of our surgical treatments, looking at the whole upper airway rather than individual sections2.

We combine this with the respiratory functional grade (RFG) assessment, which requires no equipment bar a stethoscope, but is another good way to assess BOAS pre-surgery and also audit cases postsurgery3.

This assessment is also in use as a health scheme, licensed by The Kennel Club and University of Cambridge to screen dogs pre-breeding (Figure 2). We rarely operate on grade 1 dogs, which are mildly affected, as the risks and morbidity of surgery outweigh the benefits. Grade 3 dogs that are severely affected require surgery to relieve their obvious suffering.

Lesion sites vary between breeds and so does treatment. French bulldogs and pugs have more issues with their nasal cavity and nasopharyngeal area4, and we can target the nasal turbinates with laser turbinectomy or nasal coblation.

Laser turbinectomy is a technique we have been using for years and the effectiveness is documented5. It can be time consuming, though, and often results in compromise of the nasal airflow for a few days while the inflammation settles. Therefore, I tend to separate it from palate/nostril and laryngeal surgery to decrease morbidity.

A less invasive approach is coblation, where we use radiofrequency ablation to shrink the main nasal turbinates (ventral nasal conchae). I first tried this technique about 10 years ago, but the needles were too large for the dog nasal structures and I struggled.

I recently obtained a coblator with smaller hand pieces and the initial results are very promising (Figures 3 and 4). I am now treating some younger French bulldogs with coblation and nostril surgery (alavestibuloplasty), and not resecting what look like normal soft palates. Long-term follow up will be required to see if this is a successful approach, but it does seem logical.

Palate surgery is still controversial, with the more recent techniques being the folded flap palatoplasty (FFP) introduced by Findji6. I do a modified folding flap, which I like for the bulldog and French bulldog, as it reduces the thickness of the palate at the area of maximal nasopharyngeal compression. A recent paper suggested a higher wound complication rate with the FFP, but it was a relatively small number of cases and, like any surgical technique, there is a relatively steep learning curve7. A larger study found no differences in complication rate between staphylectomy and FFP8, and a third study found better immediate postoperative recovery with the FFP9.

I rescope a number of my cases and have not seen much difference between the conventional staphylectomy or FFP for dehiscence (I have seen with both techniques). We had better objective results with the FFP, alavestibuloplasty and tonsillectomy versus staphylectomy, wedge nasoplasty and tonsillectomy, though we cannot be sure which parts of the surgery were most successful2.

Other areas that have changed are the nasoplasty. I visited Prof Gerhard Oechtering at Leipzig University in 2014 and thought his alavestibuloplasty nostril technique a little brutal, but very effective. I introduced this into the Cambridge clinic and have taught it across the UK. Luckily, although the initial postoperative appearance is a little tricky, the nostrils heal beautifully if you follow the guidelines (Figures 5 and 6). A recent paper out of Cambridge showed that the alavestibuloplasty is markedly more effective than the traditional wedge resection (even if you think you are taking a very deep wedge)10.

Another area that we have improved is the larynx. For the past 10 years, I have been performing partial arytenoidectomies by removing the cuneiform processes (in addition to everted ventricles). This technique can alleviate stridor and laryngeal collapse in grade 2 and 3 collapse11. This is particularly useful for pugs with laryngeal stridor and very soft laryngeal cartilage, and may avoid permanent tracheostomies in dogs with severe collapse.

So, BOAS treatment is moving forward, as is screening to try to breed better dogs.

Any vets interested in working with health-conscious breeders can contact the author at [email protected] and she will happily book them on to the RFG course.

JANE LADLOW is one of the clinical partners at Granta Veterinary Specialists in Cambridgeshire, and a European and Royal College specialist in small animal surgery with more than 20 years’ experience in soft tissue surgery.